Evolution of government agency for sport and recreation

Evolution of government agency for sport and recreation

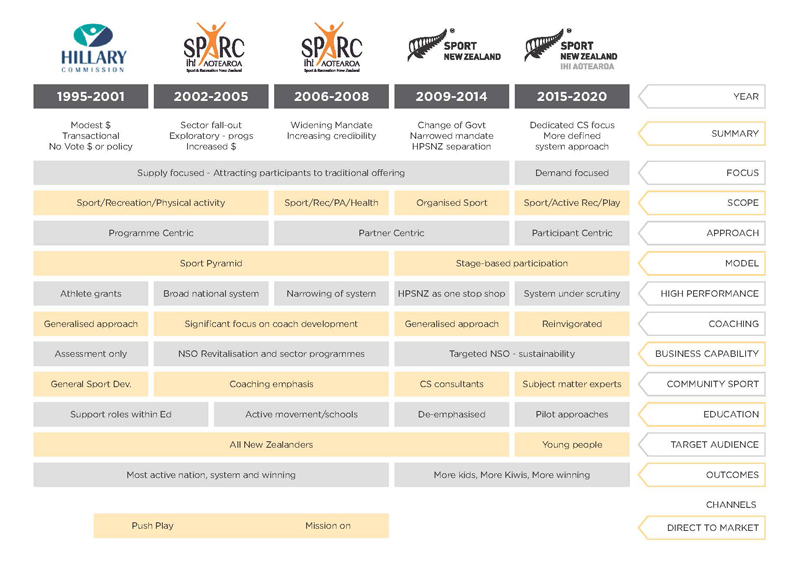

This paper provides an overview of the key shifts in direction and transition points that occurred within the government agency for sport and recreation since its inception in 2002.

Table 1 provides a summary of some of the more significant shifts.

-

Hillary Commission: 1995 - 2001

Summary:

- Modest $

- Transactional

- No Vote $ or policy

Focus: Supply focused - Attracting participants to traditional offering

Scope: Sport/Recreation/Physical activity

Approach: Programme Centric

Model: Sport Pyramid

High Performance: Athlete grants

Coaching: Generalised approach

Business Capability: Assessment only

Community Sport: General Sport Dev.

Education: Support roles within Ed.

Target Audience: All New Zealanders

Outcomes: Most active nation, system and winning

Channels - Direct to Market: Push Play

-

SPARC: 2002 - 2005

Summary:

- Sector fall-out

- Exploratory - progs

- Increased $

Focus: Supply focused - Attracting participants to traditional offering

Scope: Sport/Recreation/Physical activity

Approach: Programme Centric

Model: Sport Pyramid

High Performance: Broad national system

Coaching: Significant focus on coach development

Business Capability: NSO Revitalisation and sector programme

Community Sport: Coaching emphasis

Education: Support roles within Ed. & Active movement/schools

Target Audience: All New Zealanders

Outcomes: Most active nation, system and winning

Channels - Direct to Market: Push Play

-

SPARC: 2006 - 2008

Summary:

- Widening Mandate

- Increasing credibility

Focus: Supply focused - Attracting participants to traditional offering

Scope: Sport/Recreation/Physical activity/Health

Approach: Partner Centric

Model: Sport Pyramid

High Performance: Narrowing of system

Coaching: Significant focus on coach development

Business Capability: NSO Revitalisation and sector programme

Community Sport: Coaching emphasis

Education: Active movement/schools

Target Audience: All New Zealanders

Outcomes: Most active nation, system and winning

Channels - Direct to Market: Mission on

-

Sport New Zealand: 2009 - 2014

Summary:

- Change of Govt.

- Narrowed mandate

- HPSNZ separation

Focus: Supply focused - Attracting participants to traditional offering

Scope: Organised Sport

Approach: Partner Centric

Model: Stage-based participation

High Performance: HPSNZ as a one stop shop

Coaching: Generalised approach

Business Capability: Targeted NSO - sustainability

Community Sport: CS consultants

Education: De-emphasised

Target Audience: All New Zealanders

Outcomes: More kids, more Kiwis, More winning

-

Sport New Zealand: 2015 - 2020

Summary:

- Dedicated CS focus

- More defined system approach

Focus: Demand focused

Scope: Sport/Active Recreation/Play

Approach: Participant Centric

Model: Stage-based participation

High Performance: System under scrutiny

Coaching: Reinvigorated

Business Capability: Targeted NSO - sustainability

Community Sport: Subject matter experts

Education: Pilot approaches

Target Audience: Young people

Outcomes: More kids, more Kiwis, More winning

Pre 2002

Sport and recreation’s perceived effectiveness in promoting health and instilling moral character has seen it endorsed by tribal, political, religious, educational, commercial, and sporting leaders throughout the past 150 years.

Central government initially had little involvement in sport and recreation, tending to adopt an arm’s length relationship, and considering sport to be the responsibility of individuals and volunteer groups. It was not until the election of the first Labour Government in 1935 that the State became actively involved with the passing of the Physical Welfare and Recreation Act 1937 - responding to concerns at the low level of fitness of young New Zealanders and implications this had for defence. The Act provided for funding to local government for sports facilities but was clear that there was to be no interference in the activities of established sports. This less interventionist approach was adopted by the long serving National Party from its election in 1949.

By contrast central government has been increasingly involved in sport and recreation since the 1970s, although support and philosophy fluctuated according to which party was in power. While Labour supported strong involvement and sponsored the three key legislative milestones since the 1970s, National opposed any extension of government’s welfare role within recreation and sport.

The first of the milestones was the 1973 Recreation and Sport Act which led to the establishment of a Ministry and a Council for Recreation and Sport. The second was the 1987 Recreation and Sport Act (subsequently renamed the Sport, Fitness and Leisure Act in 1992), stemming from recommendations in the Sport on the Move Report that saw the Ministry and Council replaced by the Hillary Commission. The third was the Sport and Recreation Act 2002 which arose from a Sport, Fitness and Leisure Ministerial Taskforce and its report Getting Set for an Active Nation. It saw the Hillary Commission superseded by Sport and Recreation NZ (Sparc).

These changes in legislation reflected a growing interest by Government in sport and recreation fuelled by the professionalisation of sport, the growth of broadcast coverage, the weakening of physical education in schools and lifestyle changes such as increased trading hours and more women in the workforce.

Limited funding to the Council for Recreation and Sport which forced it to focus on small-scale programmes and development strategies was replaced from 1987 onwards with increased funding from the taxpayer and lotto (a national lottery introduced to fund sport). This provided subsequent government agencies with the necessary leverage to exert greater influence and shape the sport and recreation sector through their strategies and programmes.

The legislation setting up the Hillary Commission and Sparc, and the reports they were based on, both had a strong ‘development through sport’ flavour. They were emphatic about the benefits of physical activity and importance of community sport to achieve a range of non-sporting societal outcomes. The report leading to the 1973 Act stated that to retain its right to public funds, sport must acknowledge and accept its responsibilities in the areas of community health, welfare, and social integration. The Sport on the Move Report promoted the challenge for all New Zealanders is to be more physically active and for Government to invest in strategies to support this. It was believed that increasing physical activity through sports participation would have significant public benefits, especially for health, but also social cohesion, crime prevention and an enhanced sense of identity and image.

Other significant structural changes ahead of 2002, included the creation in 1978 of the New Zealand Sports Foundation (set up by group of businesspeople to support elite athletes), the New Zealand Sports Drug Agency (now known as Drug Free Sport New Zealand, with principal purpose, to implement and apply the World Anti-Doping Code) in 1994, the Office of Tourism and Sport in 1998 (policy advice to Minister) and the Academy of Sport in 2000.

2002-2005

In 2002 Sparc was formed by the merger of the Hillary Commission, NZ Sports Foundation and the policy arm of the Office of Tourism and Sport. Its formation was recommended by the Ministerial Taskforce of Sport, Fitness and Leisure in 2001 and reflected in the Sport and Recreation Act which was passed in 2002 (after the entity had commenced operating).

The starting point for Sparc was characterised by the challenging task of amalgamating three different organisations, meeting stakeholder expectations that were very high because of the review recommendations and the subsequent broad mandate reflected in the functions of the Act.

Like the Hillary Commission and the Sports Foundation Sparc was oriented towards high-performance and delivering national physical activity programmes through regional sports trusts (RSTs). It aspired for New Zealand to be the most active nation, have the most effective sport and physical recreation system, and have athletes and teams winning consistently in events that matter to New Zealanders.

The high-performance focus was on developing a national system and initially was broad, involving 19 national sport organisations (NSOs), 880 athletes and 250 coaches. Investment was increased during this period from $16m to $32m per annum, and prime minister scholarships, performance enhancement grants and the sports tribunal were introduced.

Sparc concentrated its early efforts in three broad areas: investment; relationships; and programmes. Its investment focused on introducing greater contestability; new multi-year, outcomes-based contracts; the disestablishment of the community sports fund (a population-based fund to all territorial authorities), and a switch from elite athlete directed funding to targeted NSO funding. This resulted in a shift in mindset governing the way in which sector funding was administered, and funding decisions made. Previously funding had been annual and output focused. This created some unintended consequences.

In seeking to demonstrate a strategic shift from its predecessors Sparc identified 10 sports as sufficiently important to New Zealanders to warrant greater attention from it (10 Priority sports – rugby, netball, cricket, golf, equestrian, yachting, rowing, cycling, swimming, athletics). The Priority Sport Strategy that sought to develop strategic alliances with sports that matter the most was one of two foundation strategies of Sparc. The other was the replacement of the Community Sports Fund with a more strategic approach.

Both these foundation strategies resulted in significant relationship issues, with local government unhappy about their long-run partnership being abruptly ended, NSOs including Māori sports organisations were unhappy about not being prioritised, and recreation and Māori/iwi organisations continuing to feel undervalued. Sparc introduced a relationship management model in 2004 to win back the goodwill and cooperation that had been lost with NSOs. This was successful and the model was subsequently extended to include RSTs, national recreation organisations (NROs) and Councils from 2006.

The creation of funds for Rural Travel, followed by Active Communities, assisted with the relationship rebuild. The latter was a fund that territorial authorities (TAs) and others could apply for that encouraged them to be innovative and collaborative in formulating new approaches to getting communities to become physically active.

NSOs became the only channel to elite athletes and teams and were therefore associated with elite success and the effective sport system aspiration. The latter resulted in the focus on NSOs being geared around building their capability, with significant investment and resource directed to improving governance, leadership, planning, human resources, and technology.

Cycling, swimming, and athletics were termed revitalisation sports, important but in need of capability assistance to make them more fit for purpose. Tennis was added as a fourth sport in need of revitalisation in 2006. These were the forerunners to commissioning comprehensive independent reviews of national bodies (such as rugby league, swimming, cycling, boxing, and water safety).

Complementing the revitalisation approach, was a sector-wide bench-mark assessment of capability. This promoted a sector focused response with emphasis on delivery of seminars and production of resources to teach and share good practice, and the development of a CEO leadership programme in 2006.

The capability focus also extended to RSTs, with a 2004 review of capability leading to increased core funding from $12m to $14m, a three-year funding commitment, and directing their focus on achieving two of Sparc’s key outcomes: to increase regional participation by 5% over three years; and to strengthen regional sport and recreation systems. Limitations with the NZ Sport and Physical Activity survey meant the former outcome could not be measured and was dropped.

NROs were not identified as one of Sparc’s original priorities despite the recommendation from the Taskforce for greater active involvement in recreation and an enhanced awareness of the outdoors. Sparc’s early emphasis was simply on retaining funding levels and shifting NROs to multi-year contracts, with the exception being the introduction of the Hillary Expedition Fund to inspire New Zealanders to seek their own adventures and experience the benefits that the outdoors had to offer.

Engagement with Māori was also not prioritised even though the Taskforce had advocated strongly for the active promotion of Māori physical recreation and the fostering of traditional Māori physical activities.

The Hillary Commission had established the first Māori Advisory Board in 1998 and a National Rōpū Manaaki in 2000 to lead stronger engagement with Māori. However, momentum with this and a successful budget bid in 2000 to encourage Maori participation in physical activity (He Oranga Poutama), was stalled as Sparc did not demonstrate commitment to the Taskforce recommendations. This gap between obligation and action was confirmed in a 2005 Sparc commissioned Gaps Analysis that found the “obligations, intentions and commitments of Sparc had not been either well interpreted in the organisation, or well understood”.

Poor understanding also impacted the policy function the new Act had provided Sparc (unusual for a Crown Agency), resulting in it being significantly underplayed during this period. This resulted in limited connection with government agencies or involvement in policy development. The exception to this was a memorandum of understanding in 2004 with the Ministries of Education and Health that guided inter-agency collaboration on the promotion of physical activity and healthy nutrition, and policy amendments to the National Education Goals and National Administrative Guidelines for schools, giving heightened priority to physical activity and requiring schools to develop competence and give priority to the delivery of physical activity for students. Both were greatly assisted by the Minister (also Minister of Education) and became the forerunner to Sparc using powerful Ministers to advance its agenda rather than via agency collaboration.

Sparc was initially very programme focused, largely a response to the key recommendations from the Taskforce. However, there was also a sense of urgency to spend its growing baseline funding (vote funding was added to 20% of lotto profits, sequenced at $0, $0, $20m, $30m, $40m over five years from 2002) and the creation of programmes was a means of achieving this.

Among the plethora of programmes were those targeting the education setting: Active Schools for primary school children (to build the capability of teachers and the school community), and Sportfit for secondary school students (school coordinators supported by regional sport directors). Both enabled Sparc to access 800 primary and 400 secondary schools.

Throughout this period Sparc continued the Push Play campaign launched by the Hillary Commission in 1999 with the objectives of getting all New Zealanders to undertake a minimum of 2.5 hours per week of moderate intensity physical activity. In response to a 2003 review recommendation to move from awareness to activation, Sparc undertook a study of more than 8,000 New Zealanders to find out about motivators and barriers to physical activity, nutrition, community facilities, obesity, and sources of health information. This led to the development of further programmes and social marketing campaigns.

2006-2008

By 2006 Sparc was well established and was gaining momentum. A 2006 restructure refocused the organisation away from a programme centric to partner centric emphasis, and increased the capacity of relationship, policy, research, and marketing functions. This was predicated on the belief that seeking outcomes from third parties required Sparc to have a stronger partnering philosophy, including into government, and that heightened focus on social marketing campaigns to get New Zealanders to become more active would activate the high awareness from the well-established Push Play campaign.

Relationships were extended beyond NSOs and RSTs to local councils and funders, and engagement plans were developed based on the unique value proposition of the partner, rather than treating them in a one-size fits all manner as previously. Investment processes became more collaborative and transparent, and investments more tailored, reflecting high trust in the partner being best positioned to know how to deliver its business. An annual conference and sector forums were introduced to further relationship building, networking and knowledge share.

Engagement with Maori continued to be sub-optimal. Despite the results of the 2005 Gaps Analysis, He Oranga Poutama, Sparc’s only Māori-focused initiative, struggled to maintain identity and focus. Inequitable gaps between iwi/Māori deliverers and RSTs were increasingly apparent, with Iwi/Māori deliverers having access to fewer Sparc resources to assist them to grow their capacity and capability. The delivery mechanism through both RSTs and Māori organisations raised issues of cultural capacity and capability of RSTs, and equity of partnership relationships from Sparc with iwi/Māori partners that held He Oranga Poutama contracts.

Despite this, He Oranga Poutama evolved from a focus on increasing the participation by Māori in sport, to one of participating as Māori in sport and traditional recreation at community level. The new goal enabled He Oranga Poutama to link strongly – but not exclusively – to Māori environments, such as marae and kaupapa Māori settings, and Māori ‘ways of doing things’, such as tikanga. ‘Traditional physical activity’ referred to activities that had cultural foundations and connections for Māori. This included better known activities of mau rakau, taiaha, kapa haka, kī-o-rahi, and waka ama (included in the 2008 Active NZ survey for the first time).

Sparc’s uncertainty with its engagement with Māori was further evidenced by its relationship with Te Roopū Manaaki, (Māori Advisory Board). Several requests by Te Roopū Manaaki for greater input into decision-making and a more authentic relationship with the Sparc senior leadership team and board were ignored, leaving members of Roopū Manaaki feeling disrespected. This and a disability advisory board were later disbanded, indicating Sparc was not yet fully open to receiving advice.

Responded to two disappointing Olympic performances, the high-performance unit commenced a new strategy that sought to narrow the system. This included discontinuing one of three academies, reducing the targeted sports to nine, and aligning 75% of funding to those sports. The number of athletes and coaches supported dropped to 750 and 150, respectively. Funding for high performance grew to $42.5m by 2008.

The focus on coaching was heightened, with increased investment and support into RSTs and NSOs via coachforce (a network of coaches funded by Sparc that operated within targeted NSOs) and the creation of a coach development framework – led by a Sparc coaching team of seven. The re-emphasis on coaching followed a loss of focus when Coaching NZ was subsumed by the Hillary Commission in 1997 and responded to the Ministerial Review identifying its key role in the development of sport.

Sparc’s reputation as an agile organisation that got results was recognised by the government rollout of the Mission-On campaign. This interagency campaign, co-ordinated by Sparc in partnership with the Ministries of Health and Education and with support from the Ministry of Youth Development, was a package of 10 initiatives designed to improve the lifestyles of young New Zealanders by targeting improved nutrition and increased physical activity. The outcomes sought were improved health, high educational achievements, and an active Kiwi lifestyle.

As Sparc was also involved in a Healthy Eating, Healthy Action strategy with the Ministry of Health that sought to improve New Zealander’s physical activity, nutrition and obesity levels, the development through sport emphasis was prominent. The opposition National Party used this as a focal point in its election campaign to question whether Sparc (and by association the Government) was operating outside of its mandate and being too prescriptive in telling people how to live their lives.

2009-2014

In response to strong criticism of the National Party before the 2008 election, and directives after it became the government, Sparc re-focused its core business to concentrate on sport for the benefit of sport.

This resulted in the discontinuation of ‘development through sport’ initiatives, such as PushPlay and Mission-On, and the transfer of others such as Green Prescription to the Ministry of Health. Policy, marketing, communications and research functions were reduced, and Sportfit and Active schools were discontinued with much of the funding redirected to a new fund administered by RSTs, Kiwisport, that sought to get more kids playing organised sport.

This refocus on ‘sport for sport’ also complemented Sparc’s other priority area of high performance sport and provided an opportunity to adopt a whole-of-sport approach to planning, support and investment in the development and delivery of sport within its NSO partners. Indeed, NSO engagement was a cornerstone of the revised operating model that positioned High Performance Sport NZ (HPSNZ) as a wholly owned subsidiary of Sparc (name changed to Sport NZ in 2012 to align with its subsidiary). In part, it was premised on successful sporting systems having aligned pathways from community through to high performance, with NSOs viewed as the common channel.

This was a period of rapid transformation for high performance. Initially a high-performance board was established to provide greater focus to decision-making. This was followed by the establishment of a single, dedicated high performance organisation in October 2011 to lead the system, via a merger of the two Academies and Sparc’s high performance unit.

A ‘one-stop-shop’ was viewed as necessary to overcome a system viewed by the Minister as fragmented, inefficient, and lacking fulltime embedded support people in areas such as sport science and sport medicine. It sought to reduce duplication and inefficiencies through introducing a shared services model, as well as providing a more consistent approach to working with NSOs in common. The government provided new investment subject to the system restructure.

A new strategy 2011-15 was developed that targeted 10+ medals in 2012, 14 in 2016 and 18 in 2020. New support initiatives such as Goldmine, BlackGold and Pathway to Podium were implemented, and $50m of infrastructure investment provided an improved daily training environment for athletes. Targeted NSOs also received increased investment and could now contract services from HPSNZ via Athlete Performance Support.

Sparc’s first strategy introduced for the 2009-14 period was consistent with HPSNZ’s strategy. Influenced by the sport for sport approach, it emphasised increasing participation in sport as an end in itself, rather than a means to an end and was a NSO led top-down approach that relied on participants being attracted to the product offering. Its goals were more kids in sport and recreation, more New Zealanders in sport and recreation, and more winners on the world stage.

The separation of high performance allowed Sport NZ to focus more strongly on community sport. A 2009 internal review of community sport described the delivery system as under pressure from social and economic change and having difficulty adapting due to a lack of clear purpose, leadership, and poor coordination of limited resources.

Sparc responded with a focus on whole of sport planning where targeted NSOs were encouraged to design national development plans, and implement these at a regional level through delivery networks of development and coaching personnel in conjunction with community volunteers, and with the strong support of RSTs. This created a strong triangulation between NSOs, RSTs and RSOs. Sparc provided new funding for community sport directors at varying levels across the NSOs to encourage alignment of support and delivery.

This approach returned RSTs to their original emphasis on increasing regional participation and strengthening regional sport and recreation systems, and again demonstrated RST willingness to align to the government agency even though they are autonomous bodies.

Sparc’s focus on community sport saw the traditional sport pyramid, (that depicts sport with a broad base of participation converging upwards through increasing levels of performance to a narrow apex of elite sport) largely supplanted in 2009 by a stage-based participant model (that identifies a sequence of stages in the psychological and physiological readiness of participants to progress from one stage to the next). Under this model elite success is predicated on talent development rather than participation numbers.

With the emphasis on sport for sport, a strong focus on corporate capability returned. A more deliberate capability approach was adopted in 2010 and tweaked in 2014. The purpose was to support the development of partners to become sustainable and capable of delivering on Sparc’s priority areas. The 2010 approach shifted the sector wide concentration to a more targeted partner focus with greater emphasis on understanding and responding to partner specific issues with tailored interventions. Initially this concentrated on governance, leadership and planning and was subsequently expanded to include people management, financial sustainability, information technology, and commercialisation. The 2014 revision placed heightened emphasis on actions that led to managing risk, and increased focus on sector-wide improvements including workforce planning and multi-partner cost reduction projects.

The launch of an Outdoor Recreation Sector strategy in 2009, was Sparc’s first significant effort to focus on NROs. The strategy’s vision was for New Zealanders to participate regularly in outdoor recreation because they understood and valued its contribution to their quality of life. It heralded the establishment of the Sir Edmund Hillary Outdoor Recreation Council (SEHORC) as an advisory body to support Sparc to implement the strategy. In its four-year tenure, it provided advice on investment in outdoor recreation, including the implementation of a contestable investment process from 2010. SEHORC was disestablished in 2013, with its advocacy and advisory role transferring to Outdoors NZ – an organisation set up by the Hillary Commission as an umbrella organisation to drive collaboration and rationalisation of the sector, that was subsequently dissolved in 2015 and its responsibilities shifted to Recreation Aotearoa.

He Oranga Poutama continued to be the flagship for engagement with Māori. A 2013 evaluation of the programme led to the introduction of an assessment tool, Te Whetu Rēhua, based on five key values important for Māori cultural and social development. However, despite this work, by 2015 He Oranga Poutama was floundering due to a lack of support and investment by Sparc. As a result, Māori and iwi providers were becoming increasingly disillusioned.

2015-2020

Sport NZ began 2015 with a third-term National Government but a new Minister who also held the Health portfolio. Its new vision was for New Zealand to be the world’s most successful sporting nation, with a continued sport for sport focus on getting more Kiwis, especially kids, into sport, and producing more winners on the world stage.

However, significant changes were occurring with Sport NZ’s approach to community sport. Fundamental among these was a shift from a supply driven approach to one that focused on better understanding what New Zealanders wanted. Correspondingly, this moved the organisation from being partner-centric to participant-centric, and recognising Sport NZ as just one of several key players in the sport and recreation system around the participant.

These changes responded to a decade of declining levels of physical activity by New Zealanders, a lack of stability or commitment to initiatives that were targeting the problem, and a failure to adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

Young people were targeted more explicitly (as opposed to all New Zealanders), and were further segmented into those with low or declining participation. This was premised on the need to change behaviours at an early age that would then have a life-long impact.

Related to this was a shift towards building the skills and knowledge required for lifelong participation by focusing on improving quality experiences for young people rather than simply increasing participation in the short-term. KiwiSport and partner funding to that point had sought ‘more’ as its measure of success. However, a new belief centred on creating a lifelong love of physical activity shifted the emphasis to quality.

This belief was reinforced by a Sport NZ review of school sport in 2015, which also promoted motivation, confidence, and competence as critical to a person being active. This holistic approach (physical literacy) led to the design of education setting interventions Play.Sport and its successor Healthy Active Learning (supported by a successful budget bid), and combined with a heightened focus on evidence and community input, were the foundations of Sport NZ’s approach to community sport.

The focus on young people also naturally led to greater attention on play and physical education as foundations of physical literacy and two domains Sport NZ will focus on increasing the levels of activity for 5-11 years-old in its 2020-24 strategy. This strategy also aspires to reduce the drop off in activity levels of 12-18-year-olds via active recreation and sport and increase the levels of activity among those within both age groups who are less active.

During this period Sport NZ also began to explore (as a direct response to a stronger focus on the participant) how it could build the capability of the system to identify, and to respond to, local need in particular in communities with lower physical activity levels.

The changes from 2014-2016 meant Sport NZ was well placed to align with the 2017 Labour led Government’s wellbeing agenda, which returned the organisation to a development through sport approach. Improved articulation of its value proposition, and development of its own outcome’s framework, linked to the Treasury’s Living Standards framework contributed to this alignment.

From 2015 Sport NZ began reflecting on its leadership role and where it could intervene in the system to impact behaviour. This reflection acknowledged its leadership role needed to evolve to be more collaborative, encouraging greater knowledge flow and connection between agents within the system, and building this capability within its partner network. This led to greater internal resource allocated to knowledge gathering and dissemination, and specific investment and capability support for insights roles within sector partners. It also led to the introduction of regional partnership managers to facilitate regional networks and alignment, the government relations role to explore collaboration with central government, the establishment of an Auckland office reflecting geographic connection with target audience and workforce, and a stronger focus on women and girls, and the disability sector.

Engagement with Māori remained problematic. The 2015 strategy again did not specifically reference Māori and iwi partnerships, and that same year, Māori and iwi providers of He Oranga Poutama (still Sport NZ’s single Māori-focused initiative) were advised that their contracts with Sport NZ were to be terminated and that RSTs would be the sole deliverers.

The resulting fallout persuaded Sport NZ to commission a review of Māori engagement. The associated recommendations led to the appointment of a Māori Participation Senior Advisor, the building of Māori cultural capability within Sport NZ, the development of a Māori Participation Plan, and the return of a Māori Advisory Group to support the development and implementation of the Māori Participation Plan.

In 2018, Sport NZ formally apologised to Māori for past decisions and behaviours that had negatively impacted on He Oranga Poutama and committed to honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

The 2015-20 period has been a challenging one for HPSNZ. After success at the 2016 Rio Olympics with 18 medals across nine sports, the high-performance system has come under scrutiny.

Athlete wellbeing and rights issues led to multiple NSO reviews, and the perceived ‘win at all cost’ culture was questioned as was the performance-based investment strategy and Olympic podium focus. The postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympics due to Covid-19 added further disruption.

A new strategy has been developed through to 2032. It promotes three new system shifts – athlete wellbeing, aspirational funding, and talent development. The latter will need to respond to a shift away from a single connected talent pathway and may require HPSNZ operating further back from elite athletes to identify talent, as Sport NZ reinforces beliefs connected to Balance is Better.

Both Sport NZ and HPSNZ learnt a lot through responding to Covid-19.

Post 2021

Sport NZ and HPSNZ have signalled their intentions to 2032, and there are consistencies in this direction with the challenges and opportunities identified in the futures work facilitated by Sport NZ.

Sport NZ’s Te Tiriti commitment statement has now become a guiding principle in the ‘Towards 2032 – Strategic Direction’.

The preferred future represents a stretch from where Sport NZ is today (and where it assumes it will be in the future if changes are not made). It also points to gaps in its current plans to 2024 such as environmental considerations.

Aligning to the preferred future will require further shifts in direction, and 2021 may be looked back upon as a key transition point for the government agency for sport and recreation.